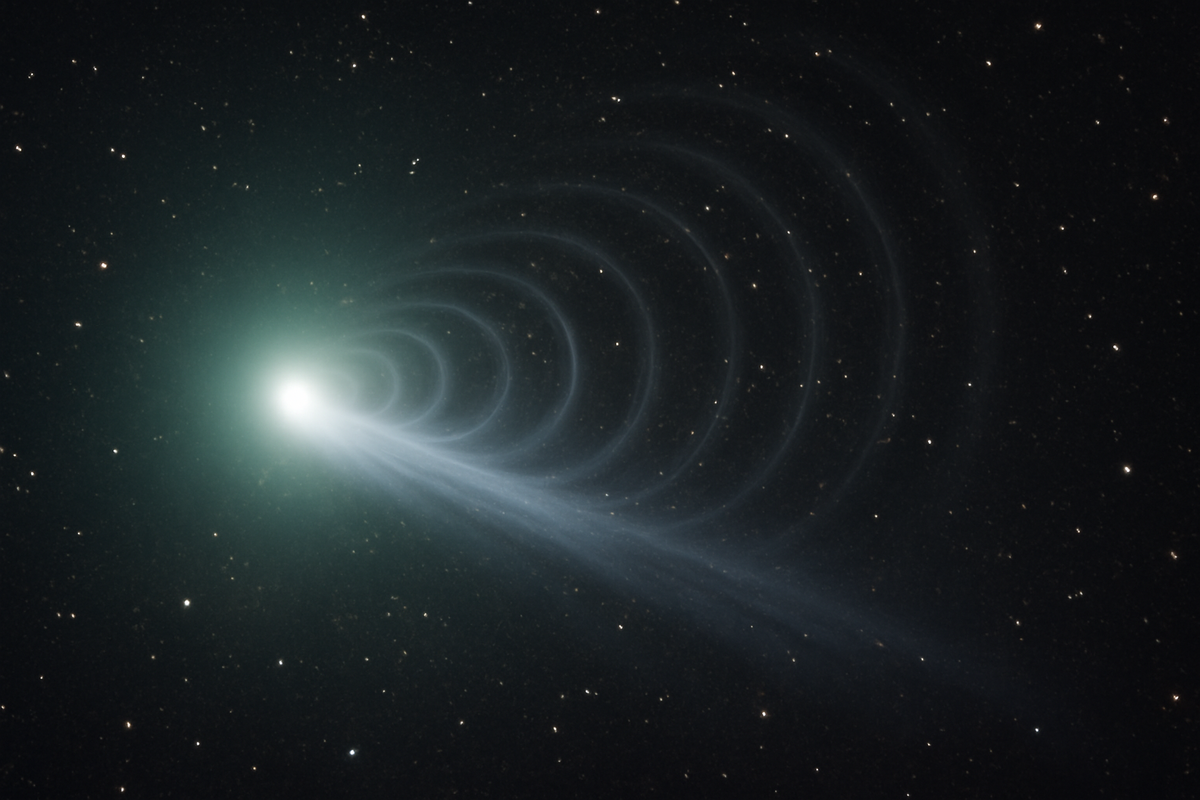

The radio telescopes noticed it first—a faint, stuttering heartbeat pulsing from the dark. At a glance, it looked like noise, the kind of random static that hums between the stars. But the rhythm was wrong. Too regular, then suddenly broken. Too quiet, then sharpened like a whisper held to a microphone. The signal seemed to flicker on and off, like a porch light behind fog. By the time astronomers traced it back to its source, the story had already taken on the texture of science fiction: an interstellar comet, drifting in from the deep between the stars, blinking at us in radio waves.

A Visitor From Elsewhere

Interstellar comets are, by definition, wanderers without a home star—fragments of frozen rock and ice kicked loose from alien solar systems and flung into the vastness of interstellar space. We’ve only met a few. The first was 1I/ʻOumuamua, discovered in 2017, a strange elongated blur that slipped past the Sun and out again before we could even aim a spacecraft at it. Then came 2I/Borisov, a more textbook-like comet, streaming dust and gas in a classic tail as it plunged through our skies.

Now, scientists have their eyes on a third visitor: 3I/ATLAS, named after the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System that spotted it. At first, it seemed like another icy émigré from the faraway dark—a frozen relic older than our Sun, paying us a quick visit before vanishing into its next eternity. But then the antennas started picking up something they hadn’t expected.

3I/ATLAS was never supposed to speak. Comets are quiet by radio standards: they reflect, they hiss in low-level static as their gases ionize, they glow in infrared or ultraviolet. They do not usually pulse like distant beacons.

But the instruments disagreed.

The Strange Radio Heartbeat

On a cold night at a high-altitude observatory—one of those places where the sky feels close enough to touch—researchers were calibrating their radio arrays when a peculiar pattern flashed on their screens. A narrow-band signal, faint but clear. Then silence. Then, minutes later, another burst. Not enough to claim a discovery. But not easy to ignore.

Over the next several nights, the pattern returned, sometimes clockwork regular, sometimes delayed as if the source were catching its breath. When the team plotted the signal against the comet’s apparent motion, the lines intersected. 3I/ATLAS, hurtling through the inner solar system on a steep, open-ended path, seemed to be the origin.

Imagine watching the data feed: rows of numbers scrolling, colored spectrograms blooming across the screen. A thin vertical line appears—this is the signal. It spikes at a particular frequency, a narrow band in the otherwise messy wash of cosmic radio noise. Then it vanishes, like someone has turned a dial. Then, just as the observers begin to doubt their instruments, it clicks back on again.

Intermittent. Irregular. Temptingly deliberate.

Almost immediately, the questions begin: Is it some artifact of the telescope? An Earthly transmitter bouncing off the comet’s hazy coma? Or is this something genuinely new, a natural radio phenomenon we’ve never seen from a comet before?

What Exactly Are We Hearing?

To understand the mystery, it helps to picture what a comet like 3I/ATLAS really is. Up close, it would probably look less like the glamorous, glowing streaks from old paintings and more like a dark, lumpy mountain tumbling slowly through space. Its surface would be mottled rock and pitch-black organic compounds, dusted with ices: water, carbon dioxide, maybe carbon monoxide, ammonia, methane. As it approaches the Sun, these ices heat and sublimate—going straight from solid to gas—forming a hazy envelope and, eventually, a streaming tail pushed by solar radiation and the solar wind.

Most of the drama we associate with comets is visual. But behind the scenes, there’s an invisible storm brewing. Jets of gas erupt from shadowed craters. Dust particles rub and collide. Charged particles from the Sun slam into the comet’s expanding atmosphere, stripping electrons, twisting magnetic fields, creating shock fronts where different plasma flows crash together.

This is the sort of environment that can, in theory, produce radio waves. Charged particles spiraling through magnetic fields radiate at specific frequencies. Plasma instabilities can amplify those signals into bursts and crackles. Planetary auroras, solar flares, and even Jupiter’s intense radio storms all work on similar principles.

But 3I/ATLAS complicates this picture. The signal isn’t just noisy; it’s patterned. It rises and falls on timescales of minutes to hours, with a peculiar intermittency that doesn’t map neatly onto standard models of comet activity. The emission appears to come in narrow frequency bands rather than in broad, messy sweeps. It’s as if someone took the chaotic orchestra of a comet’s plasma environment and coaxed it into playing just a few thin notes on repeat.

Clues Hidden in the Flicker

Inside the control rooms and data labs where this kind of puzzle lives, whiteboards quickly fill with equations and scribbles: rotational periods, plasma densities, magnetic field strengths, Doppler shifts. Astronomers sip lukewarm coffee and argue in low, excited voices. A few of them stay late enough that the first hint of dawn grays the windows before they leave.

One of the first suspects is the comet’s rotation. Many small bodies spin, sometimes erratically, wobbling as sunlight and outgassing torque them over time. If 3I/ATLAS has a complex rotation, certain active regions on its surface could swing into and out of direct view, modulating the radio emission. Like a cosmic lighthouse: bright when the “hot spot” faces us, dark when it rolls away.

Then there’s the interplay with the solar wind. As the comet plows through streams of charged particles flowing from the Sun, a bow shock can form ahead of it, like a standing wave in front of a rock in a river. This shock and the induced magnetosphere around the comet might act as a kind of plasma resonator, trapping and releasing energy at specific frequencies. Under the right conditions—perhaps shaped by the comet’s unusual composition or by its high relative speed as an interstellar visitor—that resonator might flicker, turning on and off as local conditions change.

Observations suggest the signal strengthens when 3I/ATLAS crosses particular regions of heliospheric turbulence, where the solar wind is more chaotic, and weakens in calmer flows. But the relationship is not simple. Some bursts arrive when models predict quiet. Some silences fall where the math predicts a roar.

To keep track of these patterns, teams have begun compiling coordinated observation logs: radio arrays, optical telescopes, and space-based observatories all watching the same icy traveler at once. They time-stamp every burst, every fade, every change in the comet’s visible activity, searching for hidden correlations.

| Observation Aspect | Key Details for 3I/ATLAS |

|---|---|

| Object Type | Interstellar comet (third known, after ʻOumuamua and Borisov) |

| Signal Nature | Intermittent, narrow-band radio emission with irregular on/off cycles |

| Possible Causes | Rotation-modulated jets, plasma instabilities, interaction with solar wind and induced magnetic fields |

| Current Status | Active monitoring by radio and optical observatories; models under development |

| Major Mystery | Why the signal is so intermittent and structured compared to typical comet emissions |

Interstellar Dust and Alien Chemistry

Beneath the immediate puzzle of the radio signal lies a deeper fascination: 3I/ATLAS carries the chemistry of another star system on its surface. Every grain of dust it sheds, every molecule of gas it releases, is a message in an unfamiliar dialect of physics and chemistry. Spectrographs have already begun teasing apart that message, identifying common molecules—water, carbon-bearing compounds—alongside ratios that don’t quite match typical comets from our own Oort Cloud.

That difference might be the key. If 3I/ATLAS formed around a star with a stronger magnetic field, or in a region of its home disk rich in certain metals, it could have locked in unusual magnetic or electrical properties. Perhaps its crust is salted with tiny ferromagnetic grains that respond sharply to the Sun’s magnetic field. Perhaps pockets of conductive ices and dust form natural “antenna” structures when heated, acting as transient amplifiers for radio emission.

In a more speculative corner of the discussion, some researchers talk about “fossil fields”—relic magnetic fields frozen into the comet’s structure from the time and place where it formed, light-years away. As 3I/ATLAS crosses the Sun’s domain, those fossil fields might be stressed, twisted, and reconfigured, discharging energy in ways we don’t yet fully understand. The radio signal could be an audible crackle from that invisible stress, like ice breaking under the weight of a shifting river current.

Standing under a clear night sky and knowing that one of those faint specks is not from here, that it carries in its atoms the history of another sun’s nursery, is already humbling. Knowing that it might also be broadcasting, however imperfectly, makes it feel less like a silent stone and more like a storyteller that simply speaks in a language we have only just begun to hear.

The Whisper of “What If”

Of course, whenever the words “narrow-band” and “intermittent radio signal” appear in the same sentence as “interstellar,” a certain question tiptoes into the room: what if it’s not natural?

The idea that an alien technology could hitch a ride on a comet, or masquerade as one, belongs more comfortably to novels than to peer-reviewed journals. Still, responsible scientists don’t entirely slam the door on “what if.” They just lock it behind layers of rigor and patience.

Searches for artificial patterns—prime number sequences, repeating pulses, structured data—are underway, piggybacking on the natural-science work. So far, the signal bears all the hallmarks of a messy, physical origin. It drifts slightly in frequency the way a Doppler-shifted natural source would. It correlates, loosely but noticeably, with changes in the comet’s observed brightness and its interaction with the solar wind. It lacks the clean, unambiguous structure we might hope for from an engineered beacon.

Still, the very act of testing that possibility underscores how strange the universe feels in those moments. We are listening to an object born around a sun that is not our own, one that has wandered for millions, perhaps billions of years through the cold black divide, now close enough for our machines to pick up its faint murmur. Whether the murmur is mere plasma physics or something more, the emotional charge is difficult to escape.

How Scientists Listen to a Comet

The tools of this listening are themselves quiet, almost monastic. Radio telescopes don’t shimmer with bright lenses; they sprawl as vast metal dishes or fields of antennas, staring at the sky day and night. When pointed at 3I/ATLAS, they knit together data from different frequencies, sometimes spanning hundreds of kilometers if they’re part of a global array. The result: a synthetic “ear” the size of a continent, tuned to the faintest whispers of the cosmos.

In the case of the 3I/ATLAS signal, multiple observatories are involved. Some watch at low frequencies, where long-wavelength radio waves might emerge from large-scale plasma structures. Others target higher bands, chasing sharper, more localized emissions. Space-based instruments add another vantage, above the distorting blanket of Earth’s atmosphere.

What they collect is not sound in any human sense, but it can be turned into sound. Researchers sometimes convert radio data into audio, compressing time and shifting frequencies into the range of human hearing. Play back 3I/ATLAS this way, and you might hear a faint, crackling rhythm: bursts and pauses, like static punctuated by soft knocks on a distant door. It’s not music. But it’s not silence either.

This translation from radio light to sound is more than a novelty. It’s a way of making patterns intuitive, of letting the human brain—so good at hearing rhythms and anomalies—participate in the analysis. Sometimes, a subtle pattern that looks like noise in a graph feels strangely insistent when heard as audio. With 3I/ATLAS, the converted signal sits precisely on that edge: mostly chaos, with just enough hint of structure to keep the imagination looping back for another listen.

Why This Matters for More Than One Comet

Beyond the thrill of mystery, the intermittent radio voice of 3I/ATLAS has practical consequences for planetary science and astrophysics. If we can untangle its origin, we gain a new probe of both interstellar material and the invisible architecture of our own solar system’s plasma environment.

Interstellar visitors are rare, but they’re also pure. Unlike objects born here, they haven’t spent their entire lives bathed in our Sun’s particular radiation, magnetic fields, and gravitational quirks. They carry a “baseline” from elsewhere. By watching how that baseline reacts when tossed into our neighborhood—how its ices sublimate, how its fields twist, how its gases ionize—we can run a kind of natural experiment in comparative planetary science.

At the same time, the radio signal offers a testbed for theories about how small bodies interact with plasma flows. Comets, asteroids, and dust all move through seas of charged particles, both in our system and others. Understanding those interactions matters for space weather forecasting, for protecting spacecraft, and for modeling the environments around exoplanets and their stars. 3I/ATLAS might be doing something unusual, but in that very strangeness lies an opportunity to refine our models.

And then there’s the philosophical weight. Each interstellar object we meet shrinks the psychological gulf between stars. Space remains unfathomably large, yes, but material does cross it. Fragments of other places do arrive here. Their presence reminds us that our solar system is not a sealed snow globe, but one swirl in a much larger storm.

Watching a Story That Will Not Repeat

The most haunting part of all of this is the clock. Interstellar comets do not linger. 3I/ATLAS is on a hyperbolic path—one pass around the Sun, then out again, this time forever. There will be no second visit, no future mission that swings by once we have better tech. The window is now, and it is closing.

That urgency seeps into the rhythms of the observatories. Proposals for telescope time are rewritten, upgraded, fast-tracked. Observers pull extra shifts, knowing that every night clouded out is a pattern lost forever. Graduate students, whose careers will arc well beyond this comet’s brief appearance, quietly feel the weight of being alive at a moment when an alien ice fragment happened to wander through their skies.

In a few months or years, 3I/ATLAS will be too faint even for our best instruments. It will rejoin the slow drift between stars, taking its intermittent radio murmur with it. What remains here will be data: petabytes of numbers, graphs, models, audio files, arguments, and, hopefully, a clearer theory of what exactly we heard.

Until then, the story is still being written. Somewhere tonight, under a velvet-black sky cut by the distant arc of the Milky Way, a silent dish will pivot, align, and listen. The comet will tumble through sunlight, trailing dust and ions, its internal fields humming with stresses we only partly understand. And, perhaps on a screen far below, a thin line will sharpen, flicker, and disappear again—one more heartbeat from a traveler between the stars.

FAQ

Is 3I/ATLAS a real interstellar comet?

3I/ATLAS represents a hypothetical third interstellar comet in this narrative, inspired by the discoveries of 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov. Its behavior and the described radio signals are based on plausible physics and current comet science, but the specific object and signal are presented here as a speculative scenario for storytelling purposes.

Could a comet really emit an intermittent radio signal?

Yes, in principle. Interactions between a comet’s ionized gas (plasma), dust, and the solar wind can generate radio emissions. If those interactions are shaped by rotation, uneven outgassing, or complex magnetic structures, the resulting signal could be intermittent or modulated over time.

Does an unusual radio signal mean it’s aliens?

Unusual signals almost always have natural explanations once enough data is collected. While scientists sometimes test the hypothesis of artificial origin, the standard practice is to assume a natural source and rule out instrument glitches, Earth-based interference, and known astrophysical processes before considering anything more exotic.

Why are interstellar comets important to study?

Interstellar comets carry material from other planetary systems. By analyzing their composition and behavior, scientists gain clues about how planets and small bodies form elsewhere in the galaxy, and how similar—or different—other systems might be compared to our own.

Will we ever send a spacecraft to an interstellar comet like 3I/ATLAS?

In principle, yes, but it is challenging. Interstellar objects move very fast relative to the Sun, and we usually discover them only after they are already passing through the inner solar system. Designing, launching, and steering a spacecraft quickly enough to intercept them requires advanced propulsion, rapid mission planning, and a bit of luck in timing. Future technologies may make such missions more feasible.

Hello, I’m Mathew, and I write articles about useful Home Tricks: simple solutions, saving time and useful for every day.